COMPOSITION

Exploring the art of Composition.

How to create impact in you images using using composition for harmony and retaining a viewers attention.

What is a good image and what does it consist of? Obviously good light, mood and composition. ‘Good’ light doesn’t mean it has to be bright and colourful, indeed the opposite can be true and this in turn creates the mood. A great landscape image with an interesting scene and wonderful mood created by the light can be completely ruined with poor composition.

Composition is a huge subject, there are so many ‘rules’ to follow. Though all my years of experience and teaching I have learned one thing, composition can be taught, but a good photographer has to have an ‘eye’ for it. That ‘eye’ for composition can be refined so that it comes naturally, it becomes more of a feeling with just a passing glance to so called rules, more a notion of what is harmonious and balanced and with an ability to read the landscape. Rules are there to be broken and it’s perfectly acceptable to do so, but the rules have to be understood first; breaking a rule by accident will show. The purpose of composition is to create harmony in your image and keep your viewer engaged. This quick rundown should lead-in the right direction (terrible pun intended).

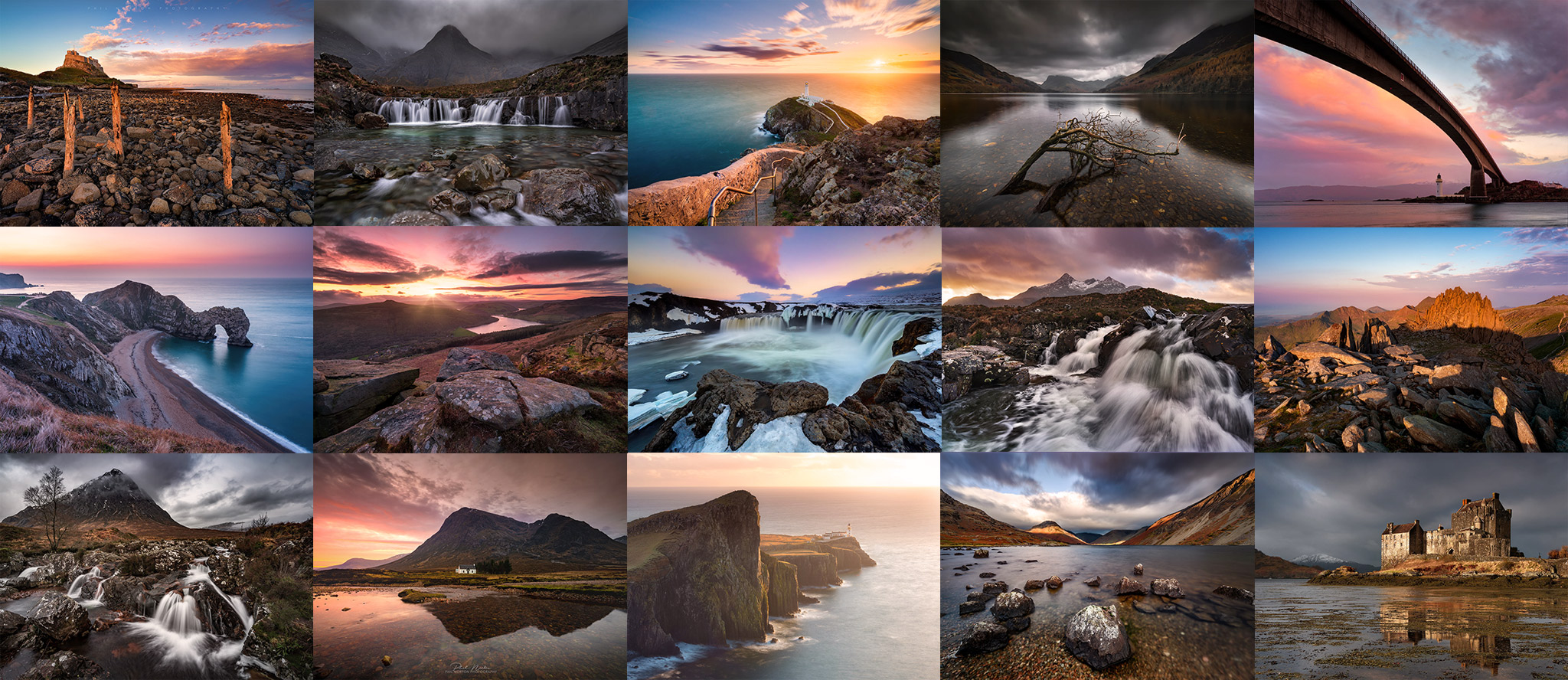

For a bit of fun to start, take a look at this grid of images (actually my personal Facebook Banner) and consider where your eye is drawn to. Some have lead-in lines, others simply use a point-of-interest. Then come back to it and see if you understand my reasoning for the compositions.

RULES AS GUIDES

All the so called ‘Rules of Composition’ should be thought of as guides, there to assist in the process but not cast in stone. The Rule Of Thirds for example shouldn’t be taken literally, it doesn’t matter if a subject is not exactly on a third at all, in fact if it isn’t it will follow the Golden Ratio more.

Understand the guides to help you but don’t obsess over them; learning to feel the scene and read the landscape will come naturally after some practice. Your composition should be quite simple based on a clear path the viewers eye should take from one part of an image to another. There may be a main point of interest with a secondary point you want to guide the viewer towards, perhaps using a lead-in line, the golden ratio, or using positive and negative space. Perhaps there is only one point of interest, or three.

Decisions you make at the scene impacts how engaged a viewer is. Lead a viewer’s eye out of the image and the composition will fail. The ‘Rules’ are not mutually exclusive; in most instances you will find once you begin to understand composition it will start to fall into place. Using a main point of interest for example, balanced with a secondary point of interest, lead-in lines will naturally start to fall into place. We can break the rules down into 6 main areas:

GOLDEN RATIO

RULE OF THIRDS

LEAD-IN LINES

POSITIVE / NEGATIVE SPACE

POINTS OF INTEREST

VIEWPOINT COMPRESSION

COMPOSITION BASICS

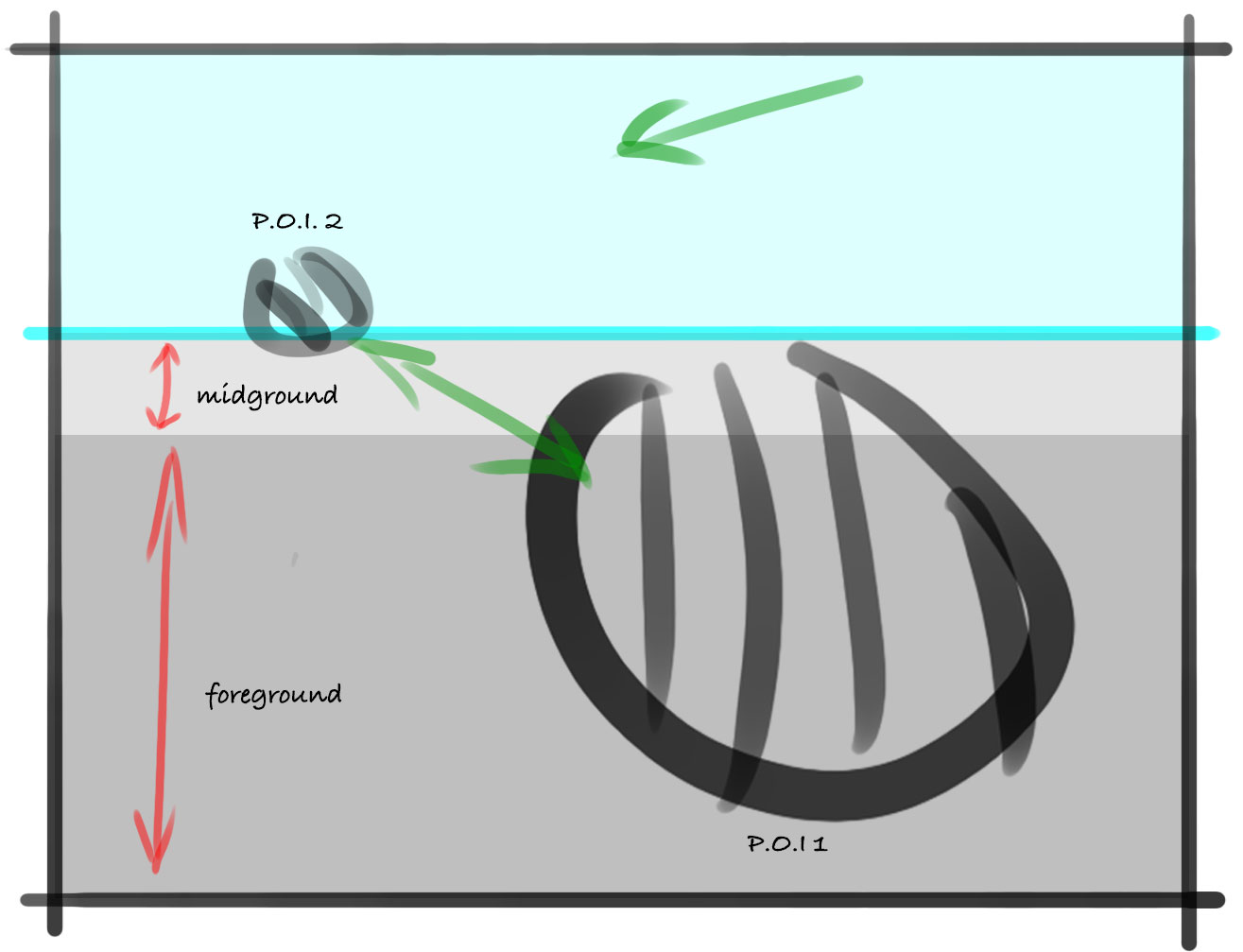

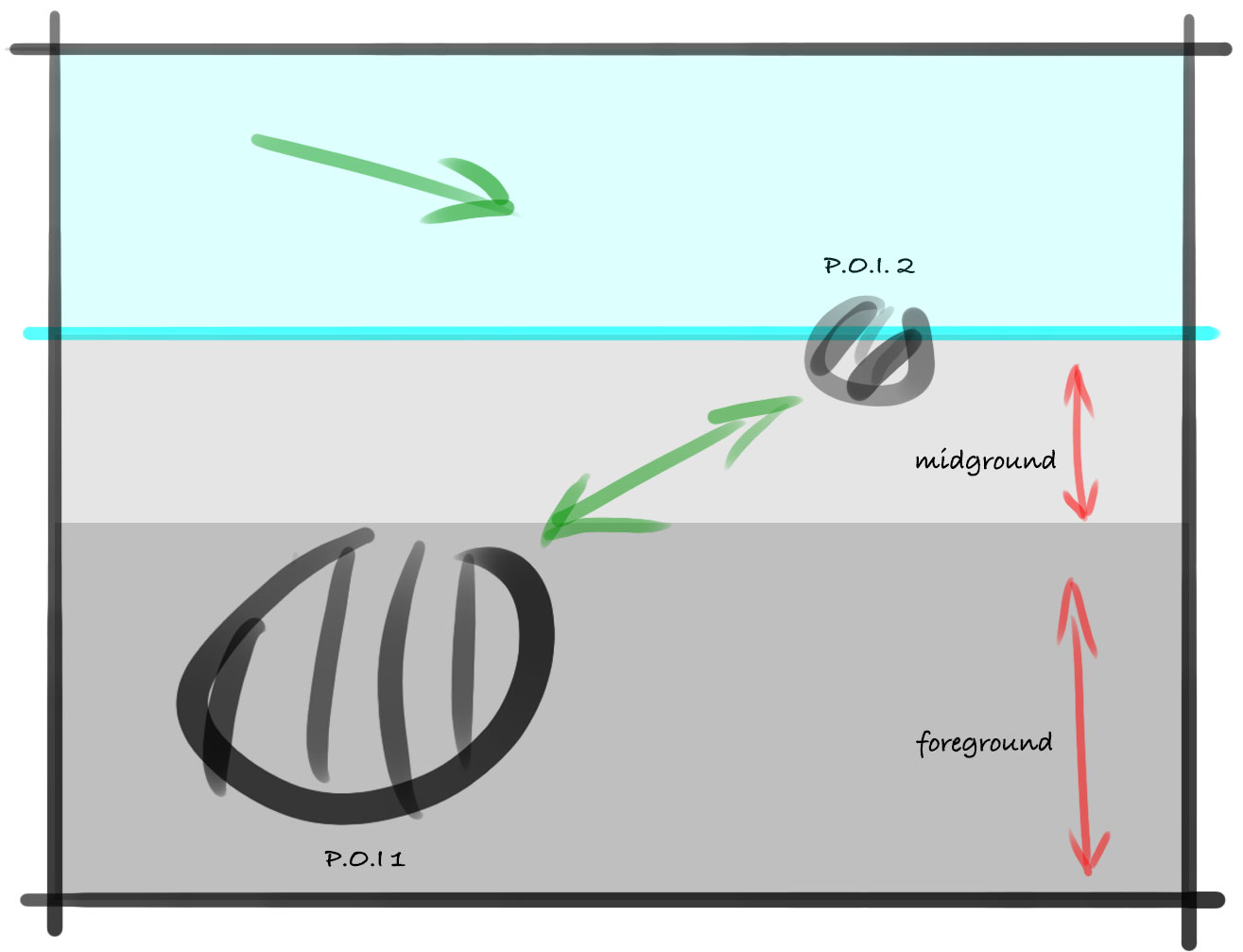

I have been teaching composition on Workshops for years and I find the diagrams below which break it down into its basics the easiest way for most people to grasp. This is composition at its simplest using two very basic principles, POI’s (Points-of-Interest) and Diagonal Opposites. Using this as a basis means you really can break composition down into very basic elements. Drag the slider to see how this simple approach can change depending on the scene.

Points of Interest – In each scene you are composing try to find two POI’s. One should be more significant than the other and will be the ‘main’ subject or the point you want to guide the viewer towards. The labels shown here, and the sizes are irrelevant they are simply for clarity. The sizes could be inverted, POI 1 or 2 could be the main subject, it really doesn’t matter, and the POI’s could be absolutely anything in the scene; a rock and a tree, a cliff edge and a lighthouse, a patch or foliage or water and a hill, a jetty and a boat, a rock in a stream and a waterfall. I could go on but you get the idea. Also ensure each POI has its own space in the frame, too close to edges and the eye can be lead out of the frame.

Opposing Diagonals – Position each POI diagonally opposite and straight away you have created a Lead-In line. Lead-ins do not have to be physical lines, they are simply parts of an image that will attract attention and direct the eye to another part of the image. It’s crucial that they are diagonal in landscape format because the eye moves more naturally across a frame on a diagonal rather than a straight line. Conversely in portrait format diagonal lines still work best but they can be directly in line one above the other, although usually the foreground POI would need to be much more dominant for balance.

Foreground / Midground – In most cases there will be as well as a background a foreground and a mid ground. How you balance these elements depends on your viewpoint height and the scene itself. You may have a distant lake in the mid ground in which case being low will compress and eliminate it, or perhaps an uninteresting mid ground where being low will focus attention on the foreground and background. The background or the horizon line may have another point of interest you can use to draw the eye back to POI 1 and create a circular movement within the frame. And with any luck you have some interesting clouds that can be used as a lead-in towards the POI.

Using this as a simple basis gives a great amount of freedom. It can be flipped the other way, additional lead-ins can be used, use 1, 2 or 3 POI’s, vary the horizon line on the upper or lower third, even use it in portrait orientation. And notice also how it will fit in neatly with the Rule of Thirds and the Golden Ratio.

GOLDEN RATIO / RULE OF THIRDS

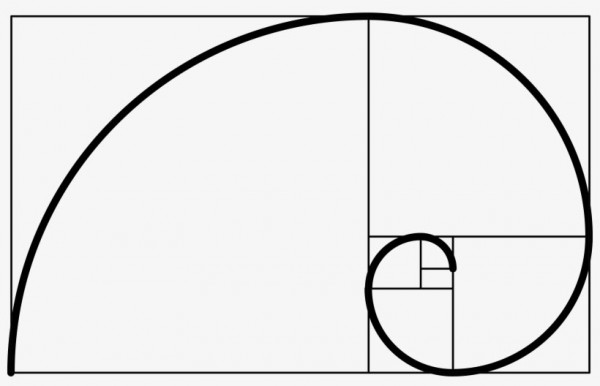

The Golden Ratio, or Fibonacci Spiral is a mathematical ratio, precisely 1.618, and represents proportions that our brains seem hard wired to see as visually more pleasing and natural, probably because it is so prevalent in the natural world too. When a curve is drawn through the intersections it creates a spiral, the Golden Spiral, which you cannot help but recognise in the shape of sea shells, plants, cells, weather systems and even galaxies.

It has fascinated architects, mathematicians and artists for centuries, the Egyptians incorporated it as did the Greeks and Renaissance artists used it too, most famously the in the portrait of Mona Lisa by Leonardo da Vinci who was fascinated with the Golden Ratio. Do a search online to see just how much it is used even today in graphic design for magazine layouts, web pages and logo design.

When a square is multiplied by 1.618 and added to it, it creates a Golden Ratio rectangle. Notice how the the rectangle fits within itself again to create further divisions all creating harmony and thus creating the Spiral. We can use these proportions and the Spiral to help with composition.

→ TIP Notice in the image below the Golden Ratio is not quite the same as Thirds. In the Menu Cog>5.Grid Settings>Displayed Grid you can select Grid #2 which does actually follow the Golden Ratio more precisely. Personally I prefer Thirds, but try it and see which you are more comfortable with.

Deer Park Pembrookshire, South Wales-Olympus 8-25mm @ 8mm

The image above taken at Deer Park in Pembrookeshire uses the Golden Spiral with the spiral landing on the headland. The curve of the foreground was included to anchor the bottom of the frame and prevent an expanse of water leading the viewer’s attention out of the shot and it echoes the Golden Spiral leading towards the headland of Skomer Island on the left. The inclusion of Skomer Island acts as a resting place for the eye, an end point as such to stop a viewer’s eye from following the horizon and going out of the scene, the intention was to provide another point of interest and to keep the eye within the frame.

The bright light from the sun is over the Thirds position to balance the sky on the right, and notice the use of lead-in lines from the streaking clouds created with a long exposure pointing back to the headland. In the mid-ground the rocks rising out of the water all appear to lean towards the right with trails of water extending away, all pointing the viewer’s eye towards the headland.

The main focal point is the centre of the image; the main headland with caves to explore visually, rocks under the water and the large rocks to the side rising out of the sea which are all placed above the lower thirds horizontal but below the centre of the image for balance. The line of the caves and the layers of rock all create another lead-in pointing towards the setting sun. Minor Points of Interest as detail help to keep the viewer engaged; in the distance a small rock rises out of the water just below the silhouette of a headland which is Ramsey Island; small detail that is not immediately apparent at first act as surprise ‘Easter Eggs’ only discovered when studying the image, they help to create engagement and discovery.

Use the overlay bar to reveal and hide the annotations and see how the composition engages your eyes. You should I hope be drawn into the image and be engaged by discovering the detail and importantly, without leaving the frame. There are elements that should bring you back into the image.

LEAD-IN LINES

Using Lead-In Lines to keep the viewer inside the frame and create depth.

Lead-In Lines are exactly as the name suggests, strong lines pointing into the image to draw the viewer in. In both of the images below it was pretty obvious what could be used as lead-ins by just using the foreground rocks and the natural lines they created. However lead-ins do not always need to be actual physical lines, it could be tones of light, colour, reflections or even how Points of Interest in a scene are balanced.

Church Rock North Devon – Olympus 8-25mm @ 8mm

Lulworth Cove Dorset – Olympus 7-14mm

Both the images above have pretty obvious lead-in lines which can be used to create depth going into the frame. Choosing your viewpoint height has to be considered carefully; too low and the foreground and lines will be compressed (see below), which may actually work. For both of these my viewpoint was around waist height with the camera slightly angled downwards to exaggerate the lines.

Roker Pier Sunderland – Olympus 12-100mm

Bamburgh Castle Northumberland – Olympus 7-14mm

Lead-in lines obviously do not have to be straight. Each of these images use a very strong curved line which leads to the main POI. The composition is very simple as it should be when there is a strong line; make it any more complicated and there is a danger of it getting diluted and losing the immediate impact.

Notice also that in each case here I have observed the Rule Of Thirds but have not adhered to it strictly. Why is that? Rules can be broken but there has to be a good reason and overall balance has to be maintained.

Roker Pier – The main POI, the lighthouse is not on a third, I wanted the viewer to stay within the frame so the lighthouse is positioned off the vertical third towards the centre. It give space to the right and encourages the eye to stay within the image, also guided by the light behind it. The horizon is very central, but not on the centre line to balance the image. I often ignore the thirds for horizons, choosing instead to place it where I feel the scene dictates, but always off centre. If a horizon is placed dead centre it will look unbalanced and will look like an image of two halves.

Bamburgh Castle – Bamburgh is tricky because the land horizon on the right slopes, even when the the sea horizon is straight an optical illusion can still make it look like the image is not level, I have even in the past compensated very slightly by tilting it up. In this case I wanted to maximise the foreground curve and remove any dead space on the right on the sand and the land mass itself. I want the viewer to stay in the image focusing on the castle, the water curve and the line of the clouds, not the space on the right of the castle.

Isle of Skye Bridge – Olympus 12-100mm

Sky Bridge – It’s obvious from this image that the curve of the bridge is the lead-in pointing in to the lighthouse for the viewer to discover. In many situations focal points can be subtle, they do not have to dominate an image. I included the cottages at the side which had some wonderful soft side light from the first light of the day, but in hind sight did I get this right?

Before you read on drag the slider to view the original image and the cropped version, which do you think works better?

I knew something was not quite right and sometimes it can be hard to identify what it is. The cottages although softly illuminated are too close to the edge of the frame and become a distraction, the small gap at the side is awkward and subconsciously attention is drawn to it, we wonder what is just outside the frame. Cropping the image to remove the cottages revealed what was truly wrong with the composition; the bridge cuts the image almost in half. The sky either side of the bridge is too equal and actually looks imbalanced when having one side larger than the other will create more harmony. Getting it wrong is fine and it is part of the process, understanding why is the key to improving.

NOT SO OBVIOUS LEAD-INS

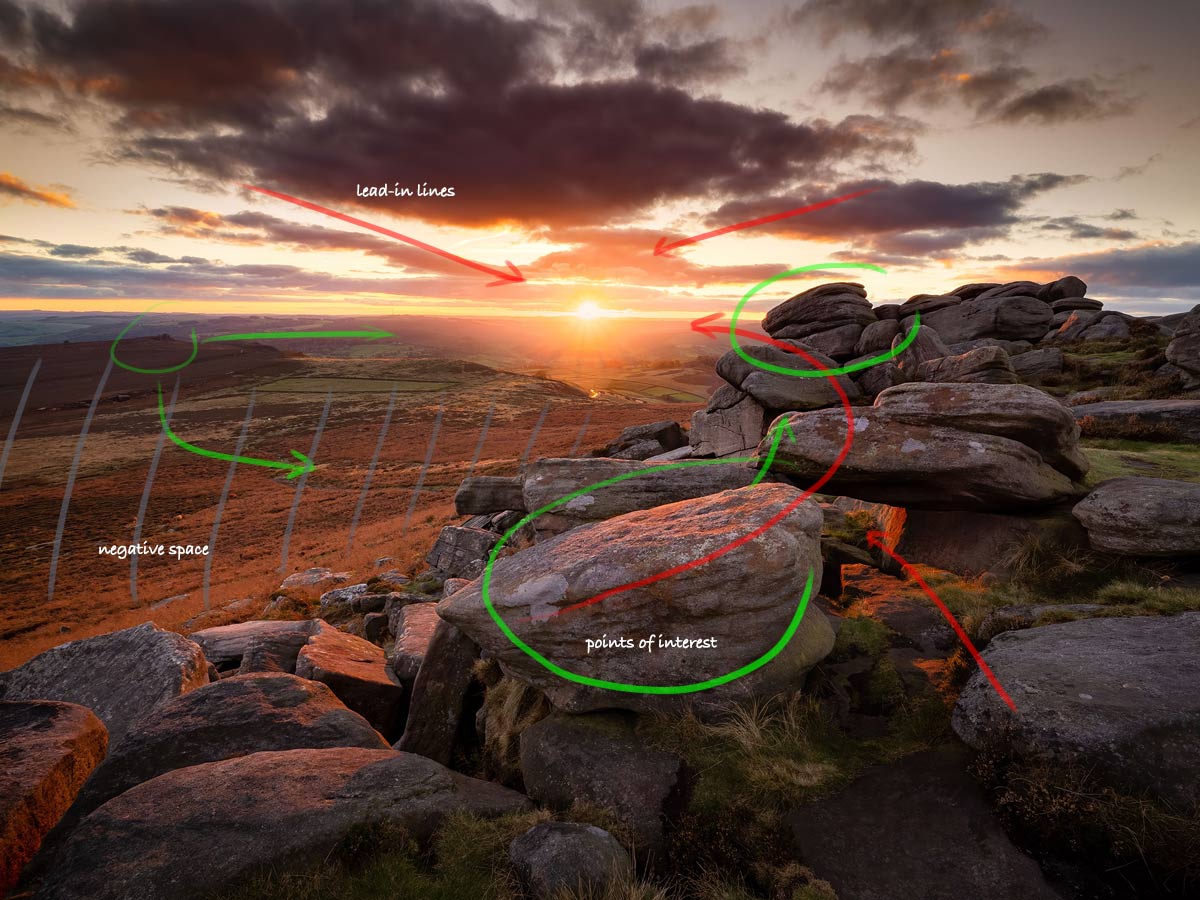

This image has a strong lead-in, guiding the viewer into the scene but it is not as obvious as the image of Church Rock and Lulworth Cove. The edge of the cliff running diagonally across the image leads the eye naturally up to the top rock placed just above the horizon. The large rock in the centre acts as a main Point-of -Interest because of the light illuminating it; it naturally leads to the rock at the top placed on the horizontal and vertical thirds. Notice the other large rocks on the bottom edge of the frame and the right corner which serve to ‘anchor’ the frame.

Peak District – Olympus 8-25mm @ 8mm

POINTS-OF-INTEREST There are three main points in this image, the rocks as mentioned above which act to draw attention in, and the sun which is a very obvious POI. A third very minor Point-of-Interest on the left, a small peak which is the silhouette of Over Owler Tor, acts as another ‘anchor’ to stop the eye following the horizon out of the frame. Small details like this can really help to keep the viewer engaged and provide discovery. Notice also there is a subtle path leading from Over Owler Tor back towards the centre of the image. Points-of-Interest can be used to guide the viewers eye, to create lead-ins and also to act as a place for the eye to stop. Imagine a written sentence on a page with a Full Stop. We know instinctively the (.) means stop, pause, end. A small detail on a horizon can serve the same purpose telling the eye to stop when it reaches it. If your image is strong enough the eye should return back to another POI without following the horizon out of the frame.

NEGATIVE SPACE The grey hatched area can be regarded as Negative Space. This is areas of an image that have little or no detail and it is perfectly acceptable, in fact is can be used to create balance and harmony in an image by again using thirds. By using Negative Space as one third, or two thirds of a scene balance is achieved with the rest of the frame which is Positive Space, or detailed. In this image there is the path, and on close inspection a few sheep grazing, all providing little ‘easter-eggs’ of discovery. The additional detail here meant I didn’t have to balance the negative space so much, but I was aware of it.

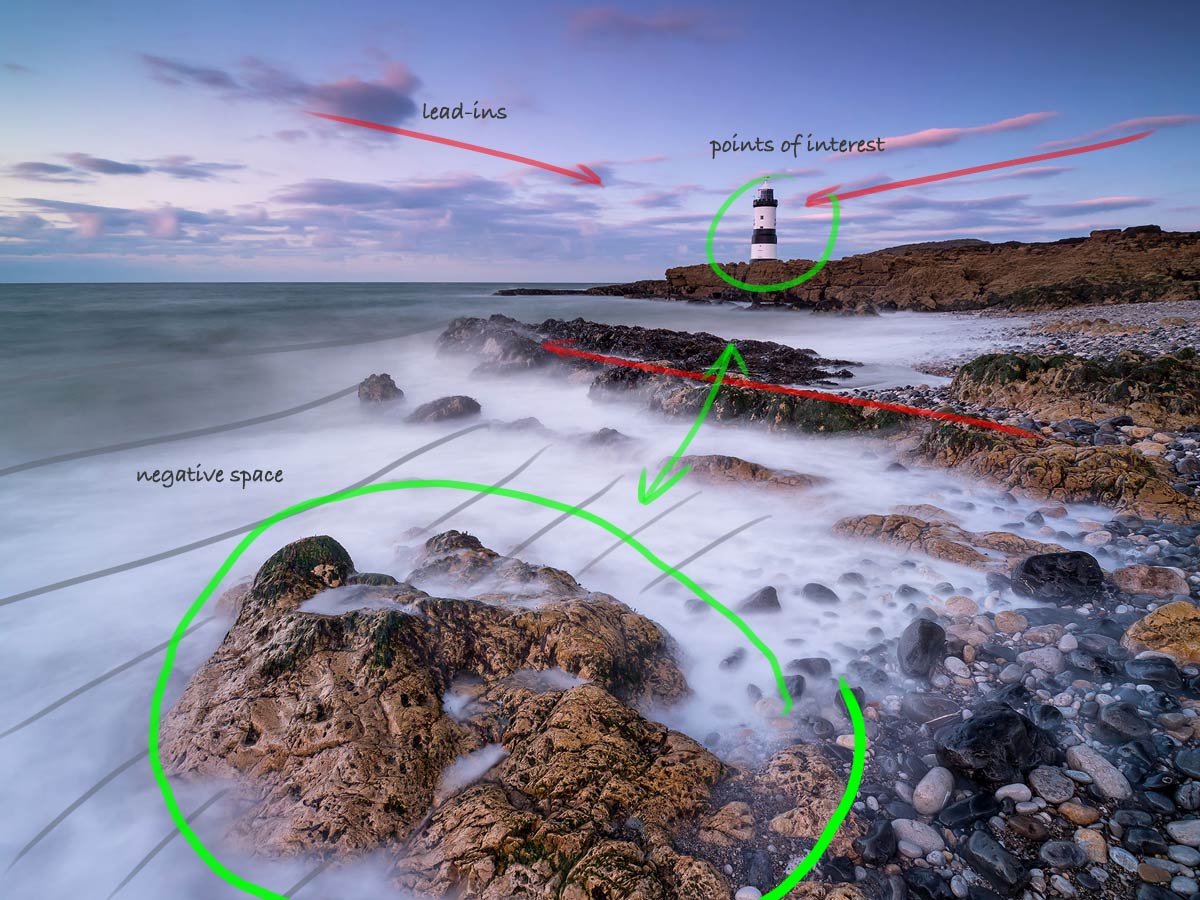

Penmon Point, Anglesey – Olympus 7-14mm @ 7mm

Analysing this image by the rules and technically it should not work but look at the image without the overlay and where is your image drawn to? Hopefully to the lighthouse itself and the large foreground rock.

Look at the rocks in the mid-ground, there is a strong lead-in line to the horizon from right to left, leading the eye out of the shot. I countered this in a number of ways; firstly the sky has enough lead-ins pointing towards the main Point-of-Interest, the lighthouse itself. Second, the negative space of the water on the right was balanced to give around 1/3rd and created a diagonal line of the rocks from the right lower corner pointing back into the frame. And third, the large foreground rock is a well defined shape because of the long exposure and positioning it on an angle towards the bottom of the frame allows the eye to move comfortably from the rock to the lighthouse. The eye moves more comfortably along angles rather than straight lines. The darker tones from the large foreground rock, the right corner, and the peninsula also form a curve naturally flowing along a Golden Spiral.

POINTS OF INTEREST

Using Points of Interest to create Lead-Ins and engagement.

Points-of-Interest are a great way to create or enforce lead-in lines. Using one main and a secondary POI, or even three, allows the viewer to explore the scene and allows you to guide where the eye actually goes. Which is the main, and which is the secondary POI? Counter to intuition, the main POI does not necessarily mean the biggest. In the image above of Penmon Lighthouse it is the lighthouse itself which I regard as the main POI; the rock in the foreground is simply foreground interest and a guide. Think of POI’s as the main and the supporting act; which is which depends on the scene. .

Rannoch Moor, Scotland – Olympus 12-100mm @ 12mm

In this image there are two main points, the rock with the detailed textures and the hill on the horizon. Positioning two POI’s diagonally opposing will create a natural lead-in. In this case the water being diagonal serves to reinforce the lead-in between the two POI’s.

Having an additional point of interest in the form of the snow covered hill allows the eye to explore and stay in the frame. Notice also how space is given to each POI keeping them away from the edges of the frame. When elements are too close to edges the space looks unnatural and there is a tendency for the eye to be subconsciously drawn to it because of the imbalance.

Rannoch Moor, Scotland – Olympus 40-150mm @ 100mm

Lake District – Olympus 7-14mm @ 7mm

KEEP IT PURPOSEFUL

Both of these images break the rules of composition. The first image has one POI and it is in the middle with the horizon almost in the centre. The second image uses two POI’s and they are both centred although the horizon is on the top third. They hardly conform to the rules and yet they work, or I feel they do anyway.

Why is this? It is acceptable to break the rules as long as it is deliberate and purposeful. You may have seen ‘lone tree’ images or minimal images of a sea groyne centred in the frame. They work because the composition is simple and very deliberate. Don’t be afraid to break the rules but you must be aware of it and have a purpose for doing so. Do it by accident and it will be obvious.

POSITIVE/NEGATIVE SPACE

Balancing Positive and Negative Space.

I’ve mentioned Positive and Negative space but what is it?

We can regard positive spaces as areas that are dominant in the image perhaps because of detail, colour or tone. Negative spaces are those that have little or no detail, or tones that tend to merge into one making any detail less significant.

In this image it is pretty obvious that the positive space is the rocks and the lighthouse, the negative space the rest of the image. Despite the subtle detail in the sky and the lead-ins pointing to the lighthouse it is similarly toned.

Balancing the spaces is best in thirds; the positive space is around a third and the the negative space two thirds. It will always create more harmony than a 50/50 split.

Sometime the positive and negative space is very obvious especially with large bodies of water and long exposures flatting it. There are time however when it is much more subtle.

Portland Bill Dorset – 12-40mm @ 20mm

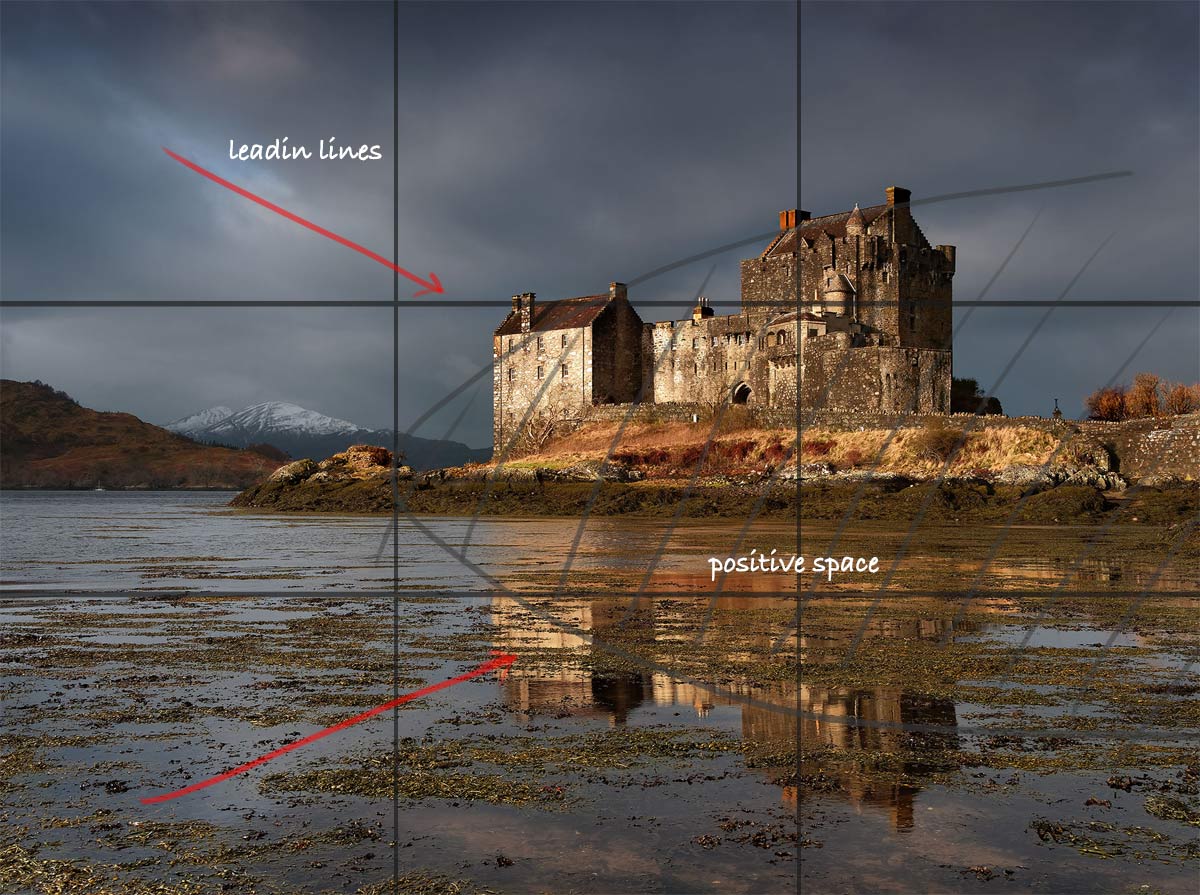

Eilean Donan Castle, Scotland – Olympus 12-100mm @ 12mm

This image of Eilean Donan Castle was a lucky break. The heavy grey sky suited the mood of the location and the warmth of the light on the castle gave some wonderful colour contrast. At low tide there was rather a lot of seaweed disturbing the reflection, but the light was strong enough to accentuate it. I was aware that the castle and the reflection are the dominant parts of the scene, the positive space. The surrounding space is negative; even with the seaweed the water becomes almost the same tone as the sky.

Making sure the main part of the castle was on the vertical third allowed me to balance the spaces, 1/3 positive and 2/3 negative. The castle takes just under 2/3rds of the space from right to left leaving 1/3 space for the snow covered mountain in the background. Watching the sky I got lucky with a subtle break in the clouds which gives a lead-in to the castle.

Problematic was the horizon, or the lack of a defined one. Is it the water line under the castle, or the water line in the background? The castle is the hero of the image and that dictated the position for me; the bottom of the reflection is near the lower edge but away from it to give space and lead the eye in. The space between the top of the castle and the top frame edge is substantially more to make the most of that wonderfully toned sky, so the ‘horizon’ falls naturally where it is. having the spaces at the top and bottom of the castle anything close to equal would have ruined the composition.

COMPRESSION

Using Compression in compositions.

When we talk about ‘compression’ we naturally think about the use of longer lenses which have an inherent quality of flattening elements of a scene. Parts of the scene in the mid or background are brough forwards and perspective is shortened dramatically, as in the two images below.

In the first image of Castle Stalker in Scotland the 12-100mm lens was used to eliminate any foreground and flatten the perspective so that the castle, the rainbow and reflections became the hero of the scene.

In the second image taken over Snowdonia from Glyder Fach the 40-150mm lens dramatically flattens the perspective and results in layering of the hills.

Castle Stalker, Scotland – Olympus 12-100mm @ 50mm

Snowdonia, Wales – Olympus 40-150mm @ 100mm

VERTICAL COMPRESSION

Compression from choice of lens should be fairly obvious, and it should be considered just as much when using wider lenses. Consider the compression of the foreground and mid ground simply by varying your viewpoint height. Getting down really low can add drama to elements in the foreground, but it will compress the mid-ground.

The image on the left of a marooned boat at Meols on the Wirral had wonderful texture in the sand which would have been more dramatic with a lower angle, but the mid-ground would have closed up more resulting in the mast being lost. In this image I should have moved a few inches to the left to allow a little more space for the end of the mast. Perhaps I will nail it next time. Being aware of the smallest detail really does matter.

The River Brathay image on the right again had to have the mid-ground considered carefully. I needed just enough space to allow for the cloud reflecting on the water and to separate the grasses; being too high would have lost the foreground detail, and being too low would have lost the separation.

Always consider your viewpoint height, perhaps you want to compress the mid-ground, or want to open it up. Think of the scene in terms of three zones, foreground, mid ground and background, and balance them to suit the scene.

Meols Beach, Wirral – Olympus 12-100mm @ 12mm

Lake District – Olympus 12-100mm @ 12mm

MOOD

It’s all about the light.

Lastly and most important of all is the light. Or the lack of it. A good image has to have mood; it should be evocative and stir an emotion, whether it is an uplifting sunset or sunrise, or a dark stormy day. The best composition is a waste of time if there is no mood. This image from Derwentwater in the Lake District was taken just as a storm kicked in. I have seen low water, high water, calm water and rough water, but I had never seen waves as rough as this. It was with wet feet.

CONSTRUCTING THE COMPOSITION

Constructing the composition means studying the scene and trying to work out how your eye will flow over the elements. It’s not likely you have a note pad to start sketching it out, or have an acetate Golden Spiral Overlay to stick your screen. You should use the viewfinder, it’s far more intimate, you’ll connect with the scene better and be more aware of intruding elements or objects.

Enable the grid in the viewfinder if it helps. Look for a main point of interest where your viewer will be most engaged with lead-in lines pointing towards it. Lead-ins do not need to be physical lines, they can simply be shapes of tone or colour, objects in the landscape, clouds, reflections or anything that will guide the eye to where you want it to be. Some lead-ins are obvious, some not so much.

Secondary Points of Interest help engagement by allowing discovery, the viewer can explore the scene and discover other elements and they should be positioned in such a way to act as a lead-in to the main focal point, and to stop the eye wandering around with no place to rest. Imagine a horizon with little detail, a viewers eye could wander off subconsciously exploring it, but with nothing to discover attention is lost and the viewer leaves the frame.

In OR Out? Elements that have been cut off by the edges of a frame draw attention because the viewer subconsciously tries to complete the whole object. Similarly elements too close to edge have spaces that are awkward and too tight in comparison to the rest of the image. Give elements their own space so the composition looks purposeful and avoid clumsy spaces that draw attention.

Negative Space usually surrounds the main elements of a scene and can be used to give balance and harmony to the image. Consider the positive space and how much negative space there is and balance the two. A third or two thirds to each usually works pretty well as a rough guide, but avoid it being equal.

CONCLUSION

Now we have had a brief look at composition and you have some images on the memory card what do you do with them? Next we will look at a processing workflow, where to start and what applications you should consider.